|

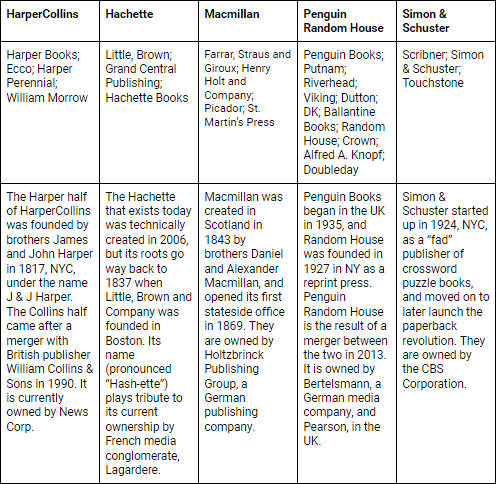

Any time you're negotiating, it pays to know everything about you can about the other party. Negotiating an author contract is no different. Even if knowing the origins of a publishing company won't come up in the negotiations, having a basic understanding of the structure and jargon can at least keep you from looking like the new kid in school. So in an effort to keep you looking like the savvy writer you are, here is the first installment of my "Publishing 101" series. Sharpen those pencils, class is in session! Fun fact: the recorded history of the publishing industry is over 1,200 years long. As you can imagine, a lot has happened and a lot has changed over that period of time. I think that as a writer, an editor, an agent, a publisher, or literally anyone within a ten-foot radius of the publishing industry, it’s good to have at least a general idea of what went down to bring us to where we are today so you don’t look dumb when someone asks you what you think of the latest merger. Obviously, 1,200 years is a lot of info for one letter—you can cover that on your own time. Instead, here’s a brief overview of the history of American publishing. Way back when America wasn’t America yet, the settlers who came over from Britain wanted to establish a body of literature in the New World. This task was made exponentially harder by the nonexistence of the Internet and the need to focus on surviving rather than writing books. There simply wasn’t time to sit down and produce quality work. So instead, those settlers brought existing books—written by the English—and printing technology. Thus, a tradition of reprinting began in Not-America, starting with The Whole Booke of Psalmes in Cambridge, MA in 1640. Keep in mind that the books being reprinted at this time were just sort of books people happened to have on hand--if it happened today, we’d be stuck all be stuck with Twilight and the Bible, probably. Americans were beginning to publish their own almanacs and political propaganda, but the good stuff (i.e. literature) was mainly coming from the British, and it was pretty few and far between. After that, things were great for a while. The reprint business was booming, sellers were making money, and everyone was happy… All the way up to the 1800s when things got shady. British authors and suppliers wised up and realized that they weren’t making much money at all from letting American printers reprint their books, so they began putting price tags on everything the Americans wanted to get their hands on. Naturally, the Americans started pirating the books instead of paying for them, since at the time the only way you could protect your work in a foreign country was to gain residency there. This situation escalated over the course of nearly a century until the International Copyright Act of 1891, which prohibited people from reprinting without permission and putting a tentative end to Americans’ shenanigans. This ended up being the catalyst that drove Americans to produce their own literature. During the late 1800s and into the early 1900s, small presses started popping up because a) it was economical as heck to run a small business back then and b) there were a ton of new stories that needed to be told. With these small presses came the first editors, who were in charge of acquiring and developing books for the presses, and the first marketers, who were in charge of selling books, usually by taking out massive ad space in newspapers and general schmoozing with the literate upper class. During this time we also saw the first literary agents, who were there to help authors navigate the industry and get their books published without getting screwed over. Before we really move into the twentieth century, let’s talk big publishers for a second. The Big Five (nee Big Six)—HarperCollins, Hachette, Macmillan, Penguin Random House, and Simon & Schuster—are the United States’ five major trade book publishing companies, and they’re basically the backbone of the publishing industry that we know today. At this point in history, these guys were still pretty young, but they were well on their way to becoming the behemoths we all know and love. Here’s a quick and dirty guide to the origins of the Big Five as well as their more famous divisions, many of which were originally small presses before they were purchased by larger companies: Further into the twentieth century, as the standard of living in America increased, books became less of a luxury and more of a commodity. People had new stories to tell, and the influx of literature drove down production costs, making publishing a realistic venture for many authors. Mail-order advertising and selling became a common method of distribution for books; in 1926 the Book-of-the-Month Club began sending books to households monthly, thus filling homes with books that might not have access to them otherwise. Penguin started publishing paperbacks in 1936, and as education standardized, more federal money went to schools and libraries. In short: people got smart, books got big, and publishers multiplied like rabbits.By the 50s, publishing was huge. Random House, Simon & Schuster, Scribner, Doubleday, Harcourt, Harper, Henry Holt, Dutton, Penguin, Viking, Putnam, Alfred A. Knopf, and Little, Brown (you’ll recognize these names from your bookcase) were all situated nicely in the industry at this point. Most of these companies were family affairs—nepotism galore—and editors would often remain with one house over the course of their entire career. This kept bloodlines pure, but it also meant that the editors at all these houses had a TON of say when it came to what got published (spoiler alert: it’s not like that anymore). This culture of editorial discretion meant that houses usually had strong editorial visions that helped guide their publishing process, but it also sometimes prevented certain voices from being heard.

Moving forward into the 60s, publishing was an incredibly lucrative field. In conjunction with good ol’ American affluence, investments in the industry from both private individuals (trade publishing) and the government (educational publishing) shot way up. The cultural and political unrest surrounding this era kept new ideas, new mediums, and new voices rolling, and America experienced something of a creative writing Renaissance; for the first time, serious attention was given to creative writing as a profession. Both in spite of and because of this literary revolution, the 60s marked an important shift in the industry’s focus; large corporations looking to diversify their portfolios began buying into publishing, and as ownership of houses traded hands, publishing became less about books and more about money. From that point on, things in publishing slowed down a good bit. During the 70s we saw the advent of the shopping mall and small chain bookstores within them. These were gradually eclipsed by big-box stores—think Borders or Barnes & Noble—in the 80s, and then by superstores like Walmart and Target during the 90s. Then, in 1995, Amazon opened its garage doors and got into the bookselling game (a pretty scummy move on Amazon’s part, but we’ll save that for another day). By 1998, the online retailer was the third-largest bookseller in America. Overall, moving into the 21st century, we saw a decline in independent bookstores and publishers becoming more reliant on big stores like B&N to push product. The publishing industry also saw a lot of acquisitions and mergers by a lot of different companies, some of which have absolutely nothing to do with books. As a result, where before there was a Big Thirteen, then there was a Big Six, and with the 2013 merger between Penguin and Random House, there’s now a Big Five, and they all sort of wash together—a side effect of conglomeration is homogenization. Don’t believe me? Try explaining the difference between a Penguin-Random House book and a HarperCollins...I’ll wait. The good thing is that the divisions, or smaller companies within the larger houses, still typically have a strong editorial focus which makes them distinct. Anyway, that pretty much brings us up to speed! We’re now seeing a resurgence of independence in publishing—editors, agents, sellers, and presses alike have begun to explore the merits of working outside of big publishing (like yours truly!), which will hopefully lead to new, interesting developments in the future. Self-publishing is now a totally viable option for those looking to avoid the stress of New York houses, and as it gets easier to source and share work, we’ve seen some great success stories in self-publishing—shoutout to The Martian and 50 Shades. We’ve got the internet, e-books, and with new technologies being developed every day, who knows what’ll happen next? I’m looking forward to finding out. Comments are closed.

|

Categories |