|

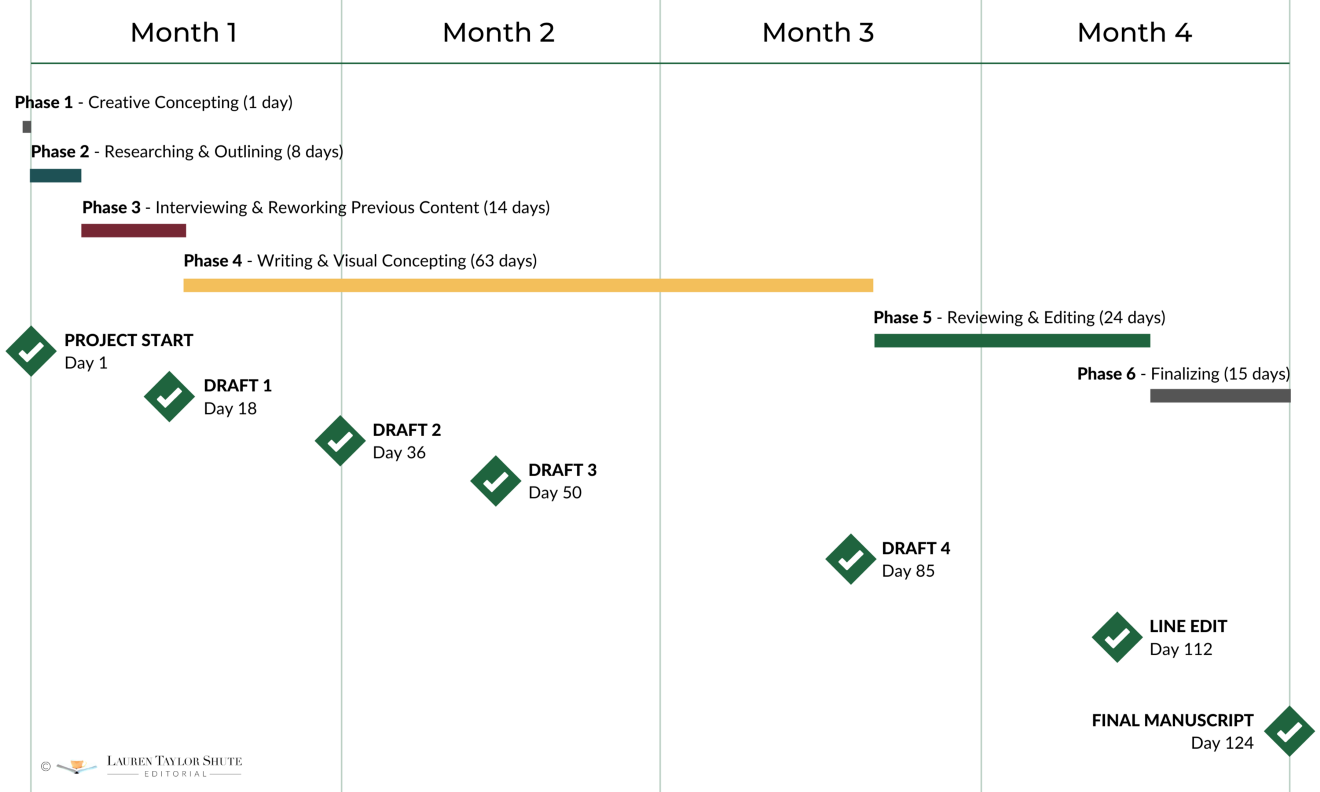

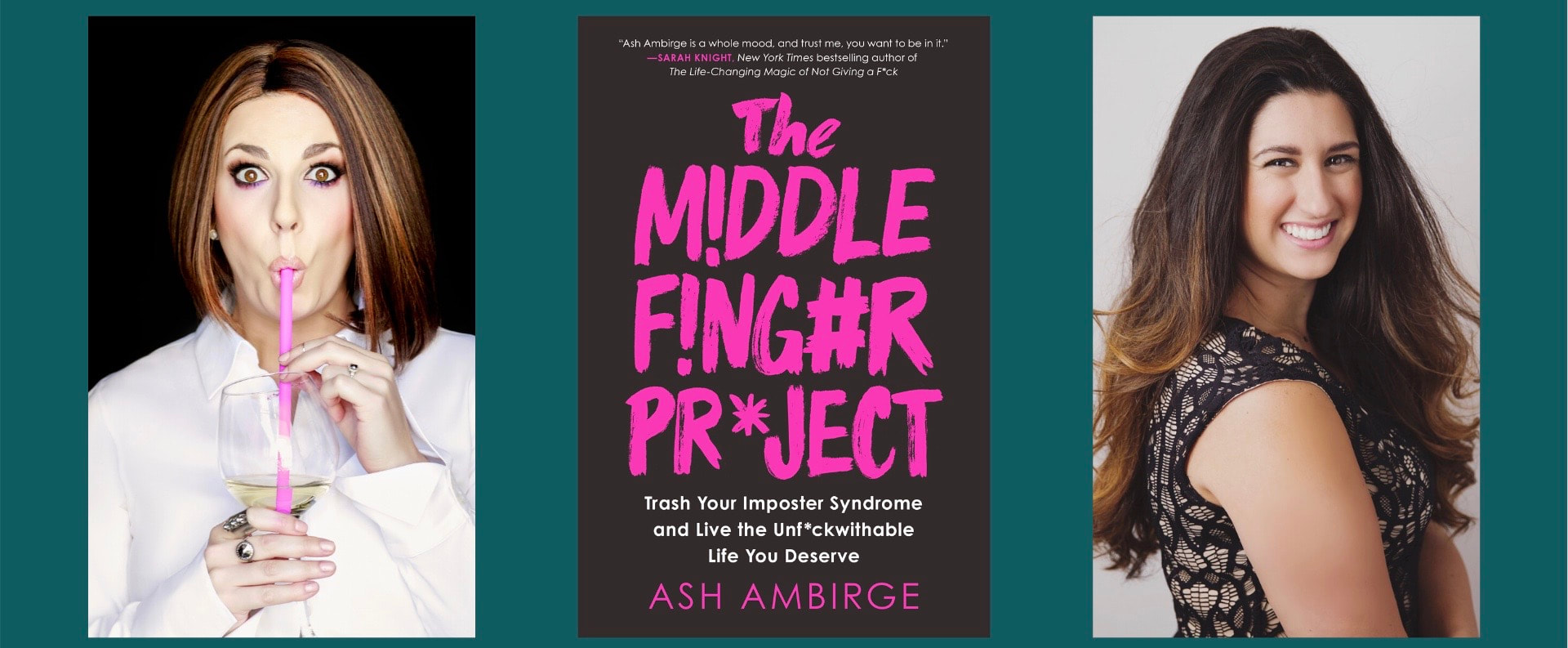

LTS Editorial recently supported an author in writing a book from idea to final manuscript in four months — you can read all about it here.

There was a lot of planning and expertise (and late nights, and wine, and...you get the idea) that went into successfully writing a book in four months, but the biggest game changer for the project’s abbreviated timeline by far was the preexisting material the author brought to the table. The author came to us with articles, notes, and even a previous draft of the book that we used to establish a baseline for his voice and to guide the strategy and concepting, which gave us the rock solid foundation we built the rest of the book on. Some of the material went unused, some things were reshaped into something entirely new, and some things were kept just as they were, but having some of his prior writing to work with and to inform our groundwork at the beginning made all the difference in the end. See, the work an author puts into writing a book is rarely confined to the words they commit to the manuscript. Your plot outlines, rough drafts, and research notes all contribute to your book in a concrete way. And beyond that, anything you write — blogs, a journal, social media posts, fan fiction, poems, love letters — feeds into your overall body of work and your identity as a writer. Your collective portfolio is a testament to what you're capable of creating, and a representation of You, the Writer. Whether or not you’ll be able to draw a straight line connecting any of that “extracurricular” writing and your final manuscript is uncertain, but you can trust that with every tweet, essay, and diary entry you create, you’re sharpening your abilities and honing your skills, and that will impact how at ease you feel working on a full-length book. So never shy away from writing whenever and whatever you feel called to, even if it’s not directly contributing to your magnum opus. It pays off to be comfortable with your craft, and the best way to do that is to write as often and as much as you can. A writer never creates something from nothing. Your previous body of work gives your book a place to start. A case study of the publishing equivalent of The Amazing RaceMy editorial firm helps people write their books, and the level of help we give ranges from book coaching and strategy to editing and/or writing full manuscripts. Writing a book is a very lengthy creative process, so projects tend to take anywhere from a few months to a few years, depending on what an author needs. We were recently faced with a challenge, though; one of our more prominent authors wanted us to help him write his soon-to-be self-published book, start to finish, in four months, with the final version ready for publication.

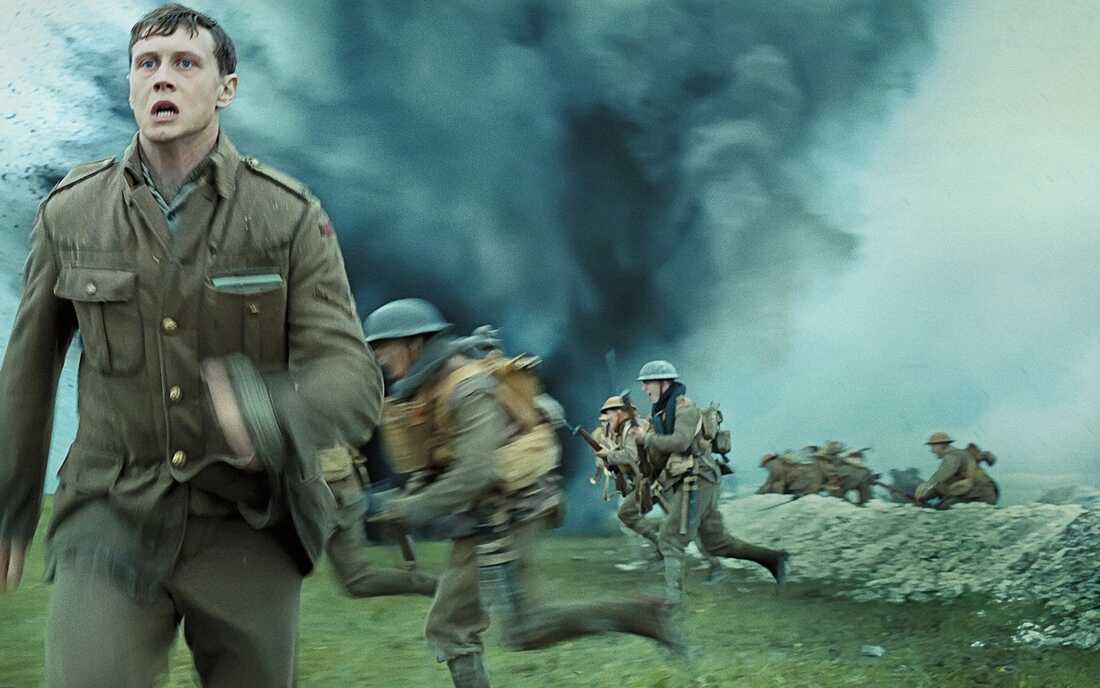

Writing a Book is a Radical Act of Self-Preservation In the face of an uncertain future, keep on writing. Since the pandemic hit, I’ve noticed myself reaching more often than not for historical books, movies, and TV shows -- most likely a subconscious effort to exchange our unstable present for the solid, dependable past. The show I’ve become most obsessed with is The Last Kingdom, a Netflix show which follows the brutal and bloody clashes between the Saxons and the invading Danish Vikings in ninth century England.

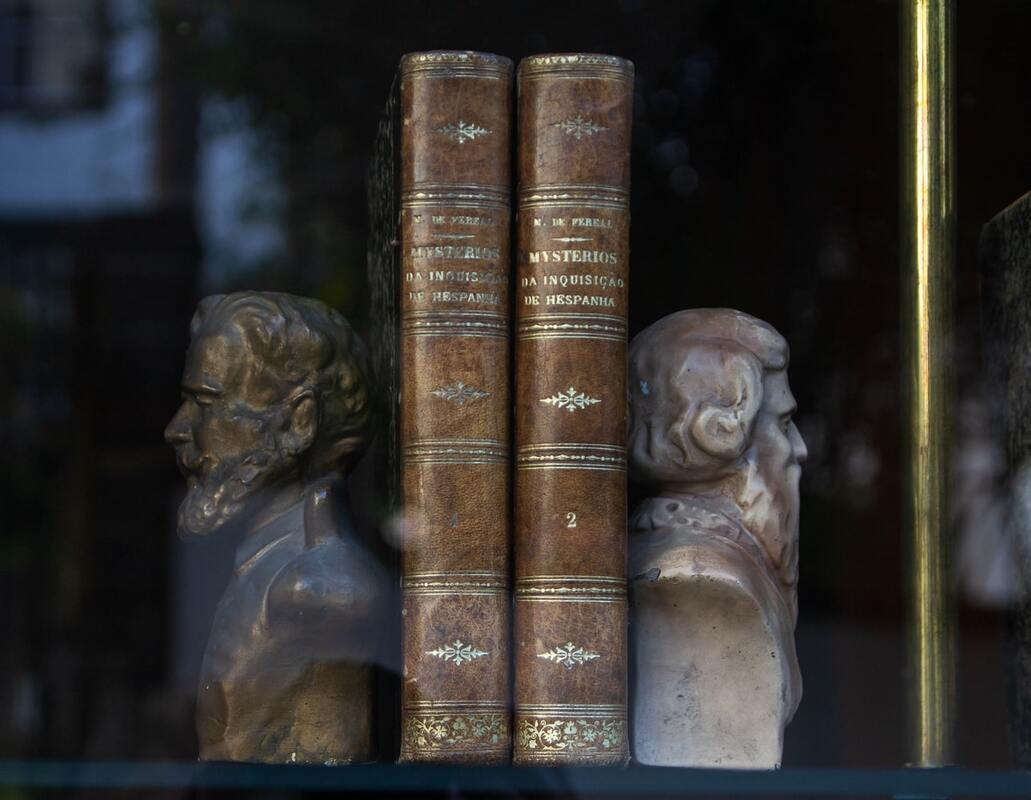

Now, this isn’t my usual type of show, but there’s a throughline that keeps me coming back. The characters speak often of how they’ll be remembered, of the legacy they’ll leave behind when they leave this life. And keep in mind, there are at least 20 deaths per episode, so death is never far behind. They don’t have long to make an impact, so they often speak of doing something so noble, their people will sing of them many years later. That is, until the king sees the power of reading and writing books. In the past, books were sacred objects, notably because they were difficult to make and barely anyone could read. Still, books were vessels for tradition, history, and ideas; they gave insight into the way things once were, as well as shaped the way things would be in the future. People looked to books for guidance on their habits, fears, faiths -- their entire worldviews. By extension, the authors of these books were extremely powerful; as only a select group of people were able to read and write, the creators of these books became the arbiters and disseminators of truth and culture. The king, much to the confusion of everyone around him, prioritizes recording his life story even while the Danes are knocking down his door. He knows that future generations will likely be able to read, and if his books can only survive the ages, they’ll know his name and what he accomplished. He makes a massive sacrifice for the future, even when his time could be spent dealing with matters at hand in his unstable present. Of course, things are different today. Literacy is the default, books are much more widely accessible, and our tools for producing written work are far more advanced and diverse than they used to be. And most importantly, we no longer rely on just a few people (or kinds of people) to tell stories. Today, a good story can come from anywhere and can reach almost anyone. It’s a testament to humanity’s drive to create that so many barriers to writing and sharing stories have been broken down over time, but it’s become so easy to read and write and consume that I think we’ve forgotten the power that stories really have. We take them for granted today because the process has been simplified and made accessible; but the innate power of books, the immutable quality that made them so significant in the past, isn’t any less than it used to be. And if we take a moment to reflect on what purpose stories serve for their authors, maybe we can better understand the value they hold for everyone else. Writers, you have a voice. |

Categories |